Caught between two giants, automotive powerhouse Thailand tries to get moving again

BANGKOK: On a taxi ride from Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi Airport to the city centre, signs of shifts in the country’s auto industry are hard to miss.

The airport taxi is likely to be a battery electric vehicle (BEV) or a hybrid (HEV), and multiple giant billboards flanking the motorway advertise an array of such marques from China.

Thailand has long been a regional powerhouse for automaking, driven by its deep connections to legacy Japanese brands like Toyota, Nissan and Honda, all of which have operated manufacturing and export bases in the kingdom for decades.

But the industry, dominated by these carmakers that manufacture more internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles that run on fuel than hybrids in Thailand, is being reshaped, analysts told CNA.

With the rise of battery-powered vehicles, the country has scrambled to adjust to the new realities of fast-shifting production chains, softening local demand and destabilising geopolitics.

“This is a big headache for Thailand,” said Patarapong Intarakumnerd, the deputy programme director of the Science, Technology and Innovation Policy Programme at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies in Tokyo.

United States President Donald Trump’s high tariffs on the global automotive sector has sent exporters scrambling to find new markets and made them cautious about the medium-term outlook for the sector.

Thailand, which was facing a 36 per cent levy on its goods, now faces a rate of 19 per cent as well as additional tariffs on the auto sector.

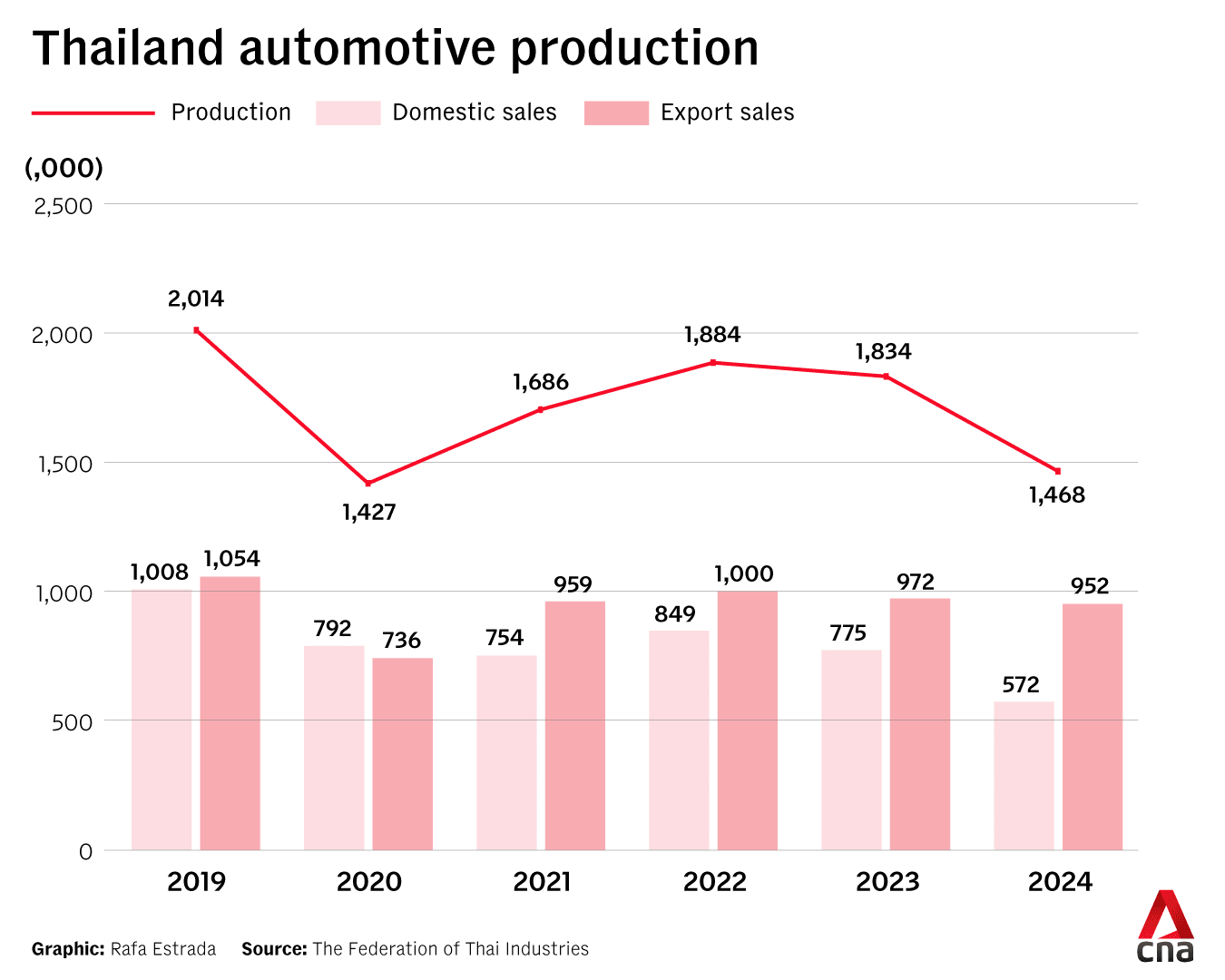

Its domestic vehicle production numbers, which declined for 21 consecutive months up until April this year, were a sign of the struggle.

But the country’s industry is showing nascent signs it may have found a new gear – latest data showed a 10.32 and 11.98 per cent increase in car production in May and June respectively, compared to the same months in 2024.

The positive numbers are “signs of recovery” for a cornerstone industry that contributes about 10 to 11 per cent of Thailand’s gross domestic product and directly employs approximately 850,000 people, said Koketso Tsoai, an automobiles analyst at BMI, a country risk and industry analysis company.

“While the industry has faced considerable headwinds, there are clear indications of resilience and strategic reorientation, particularly in the EV segment,” he said.

Much of the growth over the past two months has been due to EVs like the ones advertised along Bangkok motorways.

In June, Thailand manufactured 3,304 BEV units, a 314 per cent increase from last year. In May, the numbers were even stronger: 6,411 units, up 641 per cent year-on-year. Still, only 4.6 per cent of those were BEVs in May.

The spikes in the last two months could be the broader trend going forward, according to Narit Therdsteerasukdi, Secretary General of the Thailand Board of Investment.

“We expect automotive production in Thailand to continue to expand with fully electric and hybrid models leading the growth,” he said.

STUCK BETWEEN GIANTS

The Thai auto industry’s struggles in recent years stem from its longstanding ties with Japanese carmarkers, which have lost ground to Chinese companies leading the global EV push.

Japanese carmakers have deep roots in Thailand. They forged an industry that essentially did not exist in the country and moulded it into a hub of reliability and continental distribution in the heart of Southeast Asia.

What followed was decades of investment, strong supplier networks for ICE vehicles and process-driven excellence and training for local workers.

These have strengthened ties between the two countries and ensured the region has remained part of Japan’s backyard ever since, said Patarapong.

But it also left Thailand vulnerable – Japan’s reluctance to embrace electric batteries has flowed through to Thailand’s own inertia on EV production, he said.

“Thailand is very sticky to the Japanese. Many of the policies they’ve had or have are to take care of Japanese interests. But the Japanese, as we know, move very slowly,” Patarapong said.

“If they don't want to move fast, you cannot move that fast.”

Most of Japan’s large players opted to slowly develop the hybrid technology the country pioneered, initially popularised by the Toyota Prius in the 1990s.

The rise of the cheap EVs from China has fundamentally changed the game.

Thailand is having to balance its longstanding Japanese relationships with the aggressive expansion of Chinese firms, each with different expectations, timelines and lobbying strategies, Patarapong said.

In 2024, Chinese car brands accounted for roughly 40 per cent of new car sales in Asia and Oceania, including China itself. When it came to EV sales alone, Chinese-brand electric vehicles accounted for about 70 per cent of the market in Southeast Asia last year.

In Thailand, new car sales for Japanese brands Mazda, Mitsubishi, Nissan, Suzuki and Isuzu collectively dropped by a quarter, based on data from MarkLines, an automotive information provider.

A wave of Chinese vehicles is washing over the region, but capitalising on an industry shift characterised by shorter and more concentrated EV value chains has proven challenging for Thailand, said Pavida Pananond, a professor of international business at Thammasat University in Bangkok.

Unlike Japanese car companies, Chinese outfits are not known to cultivate local supplier networks, as they tend to be much more vertically integrated, she said.

It leaves less room for local players in Thailand, which may not be exposed to or experienced with battery production or software development, sophisticated processes necessary for EV production, she added.

“These are the items where we never had a supplier before, so we need to invite them now,” said Krisda Utamote, President of the Electric Vehicle Association of Thailand.

The issue has arisen now, though, where local demand is too low to justify investments in expensive ventures like battery production.

“It's like a chicken-and-egg thing,” he said.

It means, Patarapong said, that Thailand faces the risk of losing the one major advantage it had over its regional competitors – the number of local parts suppliers and the expertise they carried.

With EVs requiring just a fraction of the parts that regular ICEs do, these parts firms are already facing major headwinds due to the US government’s 25 per cent tariffs on the automotive sector, on top of reciprocal tariffs of 19 per cent for exported Thai goods.

The US is Thailand’s top destination for auto parts, a trade worth US$1.4 billion last year. Thailand also had significant exports to Mexico, the primary market for the assembly of vehicles destined for American roads.

Thailand exported US$358.1 million worth of passenger vehicles to the US in 2024, only 2.93 per cent of its total global exports.

DRAWING CHINESE INVESTMENTS

The Thai government has been luring investment for local production by Chinese firms like BYD, Neta and Great Wall through its EV 3.0 scheme, which has evolved into the EV 3.5 scheme, and other incentives.

The scheme has a local EV production requirement, ratioed for foreign companies at 1:1.

This means those companies are required to produce one EV locally, for each EV they want to import into Thailand.

If a company wants to start manufacturing in 2025, that ratio is 1.5:1.These stipulations will gradually become more onerous, up to a 3:1 ratio by 2027.

It also provides subsidies to consumers who purchase BEVs up to THB100,000 (US$3,100) depending on vehicle type, and lowers import duties to boost domestic demand.

Government policy aims for 30 per cent of vehicles produced locally to be zero-emission ones by 2030, a target widely expected to be missed.

Those subsidies mean EVs are competitively priced in the domestic market. And oversupply from a constant pipeline of domestic production – mandated for companies under the EV 3.0 scheme – means Thais could put off purchasing knowing they could wait for prices to drop, said Krisda.

Total EV production in the pipeline right now is about 100,000 units, he said, “which is very high, because the total electric vehicle registration last year was about 76,000”.

“If I'm considering buying an electric vehicle, I would say, well, you have plenty of supply coming up very soon. So I would not rush. I would wait until you drop the price,” he said.

“That situation is not so healthy for any car manufacturer.”

Domestic sales have struggled due to broader economic concerns and declining consumer confidence. Sales in 2024 were 56 per cent lower than in 2019.

But they have improved by around 5 per cent in May and June, year-on-year, driven especially by BEVs and plug-in hybrids, competitively priced under government incentives that lower their excise tax and offer subsidies.

With more brands in the market, however, the market has become more competitive, said Krisda.

“The total size of the cake has not increased. But it’s being divided among many more players, new competitors, new brands to the market,” he said.

“So, each brand has to really fight to keep its market share within this shrinking cake that we are seeing.”

Foreign companies on the EV scheme had not been allowed to count vehicles manufactured and exported from Thailand as part of their local production quotas.

Instead, only EVs produced in Thailand and sold locally could be counted in the production quotas.

This means they have faced the dilemma of manufacturing more cars than the local market demanded, or being unable to import other models currently not built locally.

It has contributed to the glut of local supply and weakened export numbers.

But on Jul 31, Thailand’s National Electric Vehicle Policy Committee made amendments to that policy - vehicles built in Thailand and then exported will count towards the quota.

The flexibility, it said, could result in EV exports increasing to 52,000 units in 2026, up from only 12,500 this year.

It could be a major step to helping Thailand regain its place as a key regional manufacturing and export hub, like it was in the past, Krisda said. “Exports play a much more important role in taking up the total capacity of production over many years and will still play a crucial role for us ahead,” he said.

While Thailand remains the 10th largest car producer in the world, the 1.47 million units it produced in 2024 were still below the pre-COVID-19 levels of 2019, when it produced 2.01 million units.

Thailand’s neighbours will not be slowing down in their own efforts to forge industries centred around EVs.

For Thailand, “the threats become more urgent as EVs become more significant”, Pavida said.

She noted that Indonesia is focusing more on the upstream industries like batteries and attracting investors on the back of a wealth of natural resources.

Vietnam, meanwhile, has pushed more assertively on the downstream with its own brands, unsaddled by the presence or demands of Japanese carmakers.

Thailand has sat in the middle for now, due to the legacy strength of its manufacturing, she said.

“It remains to be seen which country will come out as the winner.”

For Thailand, long mythified as the “Detroit of the East”, a comparison to the American city’s 20th-century legacy as the heart of the US auto industry, much is at stake.

Detroit became a symbol of industrial decline, unable to overcome a reliance on outdated auto technology and resistant to change and innovation. It is reason enough for Thailand to reject such a label and forge a brave new path, Krisda said.

“I don't know why they keep calling us Detroit,” he said.

“I don't really see the word ‘Detroit’ fitting in with what we see happening here.”

Disclaimer: Investing carries risk. This is not financial advice. The above content should not be regarded as an offer, recommendation, or solicitation on acquiring or disposing of any financial products, any associated discussions, comments, or posts by author or other users should not be considered as such either. It is solely for general information purpose only, which does not consider your own investment objectives, financial situations or needs. TTM assumes no responsibility or warranty for the accuracy and completeness of the information, investors should do their own research and may seek professional advice before investing.

Most Discussed

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10